Remembering Raymond Briggs

by Olivia Ahmad, Quentin Blake Centre team

We were so sad to hear of the passing of Raymond Briggs yesterday. He was a truly pioneering illustrator and a kind observer of people's lives.

When Raymond Briggs said he wanted to be an illustrator as a painting student in the 1950s, his tutors at Slade School of Fine Art were horrified. Lucky for millions of readers around the world, he went for it anyway.

Below painting comes illustration… below that comes cartoons… then, below the gutter, are the sewers – strip cartoons! Comics! Ugh! The very cesspits of non-culture.

Raymond applied to art school when he was 15, inspired by the cartoons he saw in newspapers and Punch magazine. He went on to write and illustrate books that used cartooning techniques in new ways to talk about the big stuff of life – social mobility, grief and abuses of power. He didn’t forget to have fun though: his surreal picturebooks are full of outrageous situations and subversive jokes. He wasn’t afraid to do toilet stuff either (in fact, he was one of the first to go there!). Many of his books are thought of as for children, but Raymond never saw his books as being for (or not for) anyone in particular: “Books are not missiles, you don’t aim them at anybody” he said.

After six years at art school doing these endless paintings and putting them away afterwards, showing your mum and your girlfriend and that was it, suddenly you start doing commercial work and there was someone actually waiting to see what you’ve done. On top of that, they were going to give you money for it!

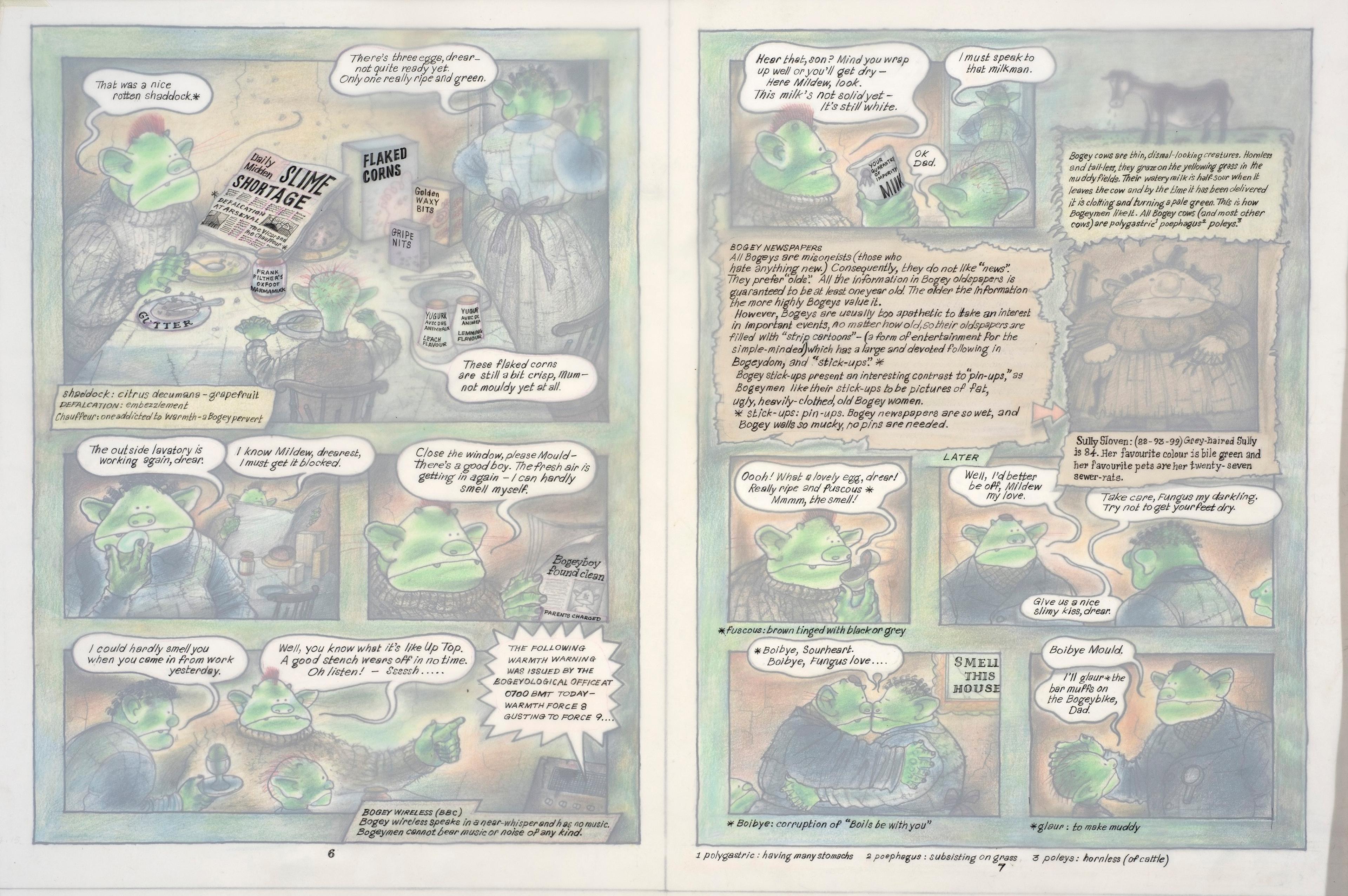

When Raymond graduated in 1957, he started looking for work with publishers. Mabel George, an editor at Oxford University Press, looked over his portfolio and asked, “How do you feel about fairies?”. It turned out he felt great about them and throughout the 1950s and 60s he illustrated many anthologies, eventually remembering fairy tales as “the finest things to illustrate... full of giants and fairies and animals talking. And they’re usually set in the past so you don’t have to draw boring modern things like cars.”

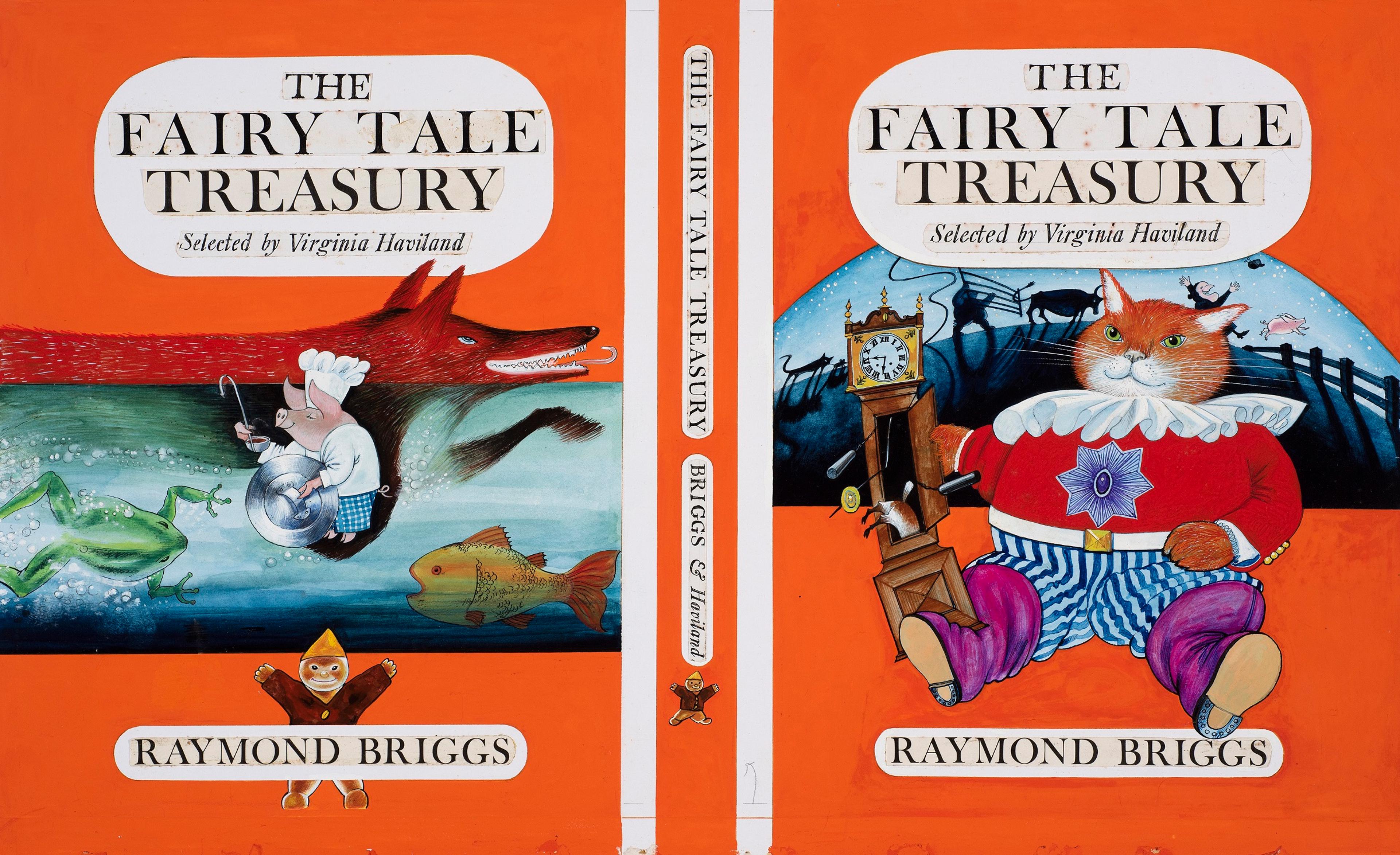

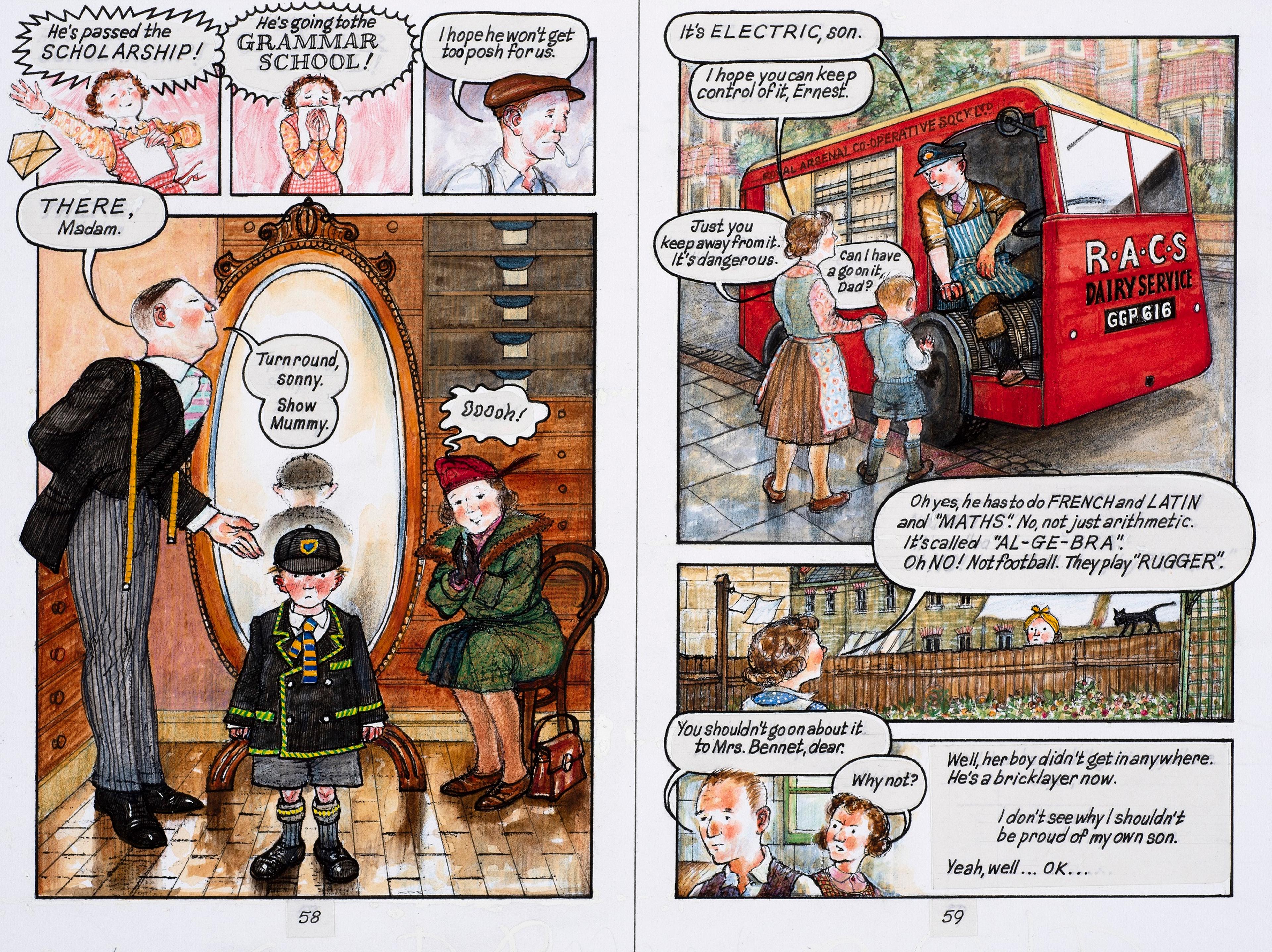

Although he loved fantasy, many of the books that Raymond wrote and illustrated were based on real life, and especially his own family. The lead character of his 1973 picturebook Father Christmas was based on his dad who was a milkman. The book was radically different from other children's literature at the time as it represented the bearded icon as a working-class man, a perspective hugely underrepresented in publishing.

His job is very much that of the working man. It is a cross between a postman, a milkman, a coalman and a sweep. It is cold, lonely, hard and dirty. No wonder he grumbles a lot.

As well as centring working-class people, the book broke new ground by using a comic strip format for frame-by-frame storytelling. This way, Raymond could fit more action into a standard 36-page picturebook.

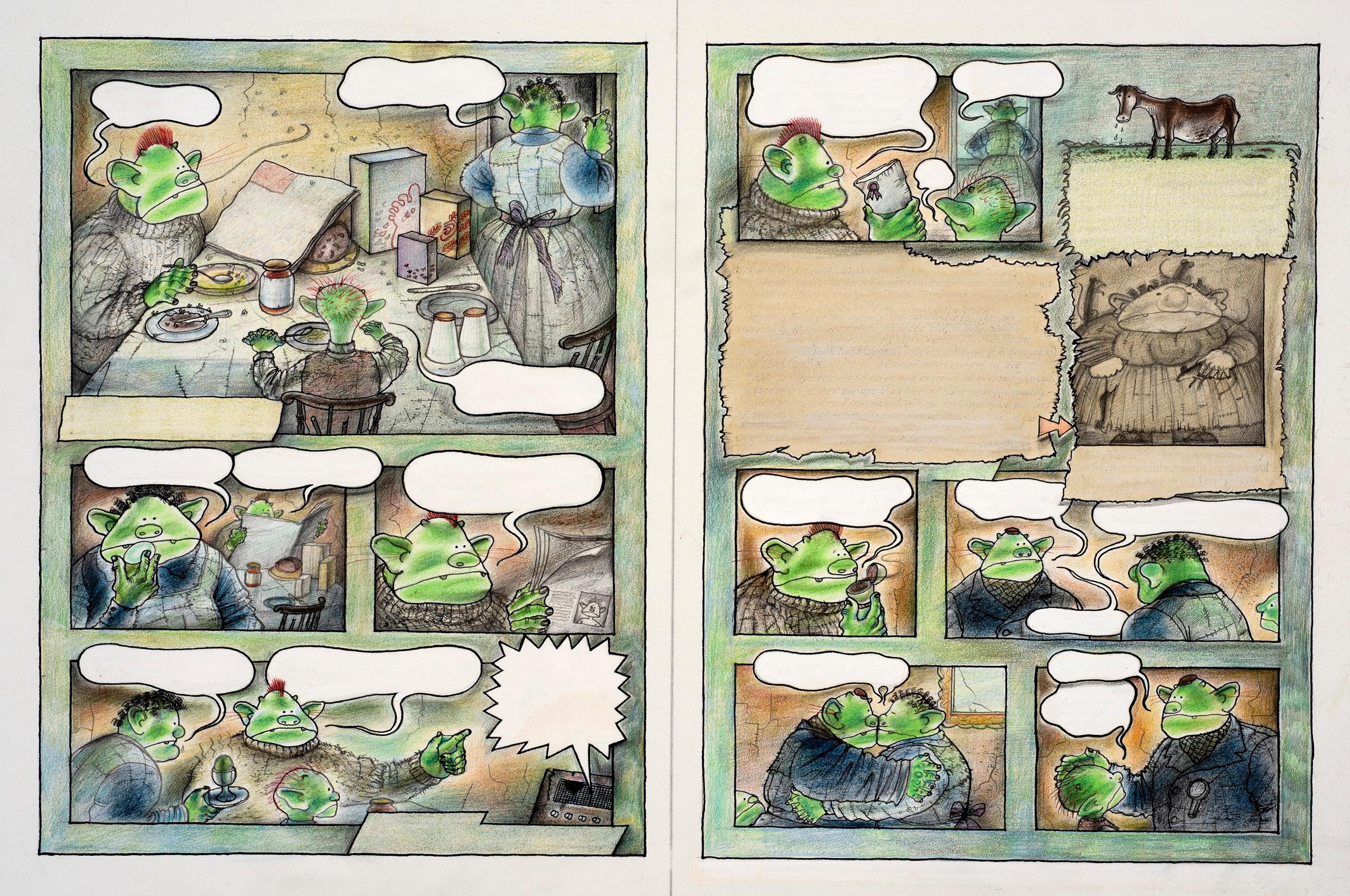

Raymond also used comic panels for Fungus the Bogeyman, a very different kind of book that started as an alphabet of 26 yucky things, but soon evolved into an obsession for Raymond. The book follows a day in the life of Fungus, a reflective mythical creature questioning his purpose in life. Raymond created an immersive world for Fungus, keeping a whole filing cabinet of Bogey vocabulary created by combing through the dictionary for “words that sounded Bogeyish or suggested Bogey ideas”. Fungus’ bathroom is called a ‘barathrum’, a Latin word meaning ‘a hellish pit’. The book celebrates all things dirty and grimy: “I wanted to show the petty nastiness of life – slime and spit and dandruff, all this awful stuff which is slightly funny because it detracts from human dignity and our pretensions… everyone’s got that in their life. Everyone has to deal with disgusting things.” Now we see books all the time that are full of the essential grub of life, but in 1977, this was a bold new idea.

Raymond’s next story was also a mixture of real life and fantasy. The Snowman is a silent book taking place in a crisp landscape: boy makes snowman, boy and snowman become friends, snowman melts away.

It was a simple idea – kid builds a snowman and snowman comes to life. It’s quite corny – things have been coming alive in children’s books forever, inanimate things.

But the book is poignant and came after Raymond experienced the loss of his wife and parents in a painful two-year period. The gentle rhythm of the story showing the growing special friendship between the two characters makes its sudden end so moving, though Raymond said “The Snowman has to melt because that’s what snowmen do.”

Raymond wrote more directly about his parents too. His graphic novel from 1998, Ethel and Ernest, follows their lives and his. The book starts with his parents’ first encounter, when Ethel waves a duster out of the window of the house where she is working as a maid and a friendly milkman on a bicycle waves back. The two married in 1930 and bought a house in Wimbledon Park where they lived for 41 years.

It’s just a book of facts, just their plain lives. Nothing extraordinary about them, nothing dramatic; no divorce or anything. But they were my parents and I wanted to remember them.

Although it’s a very personal book and evocative of its time, it has a lot to say to many people. It talks about the gap that can open between parents and their children because of social mobility, family tension and the grief that comes with death and loss.

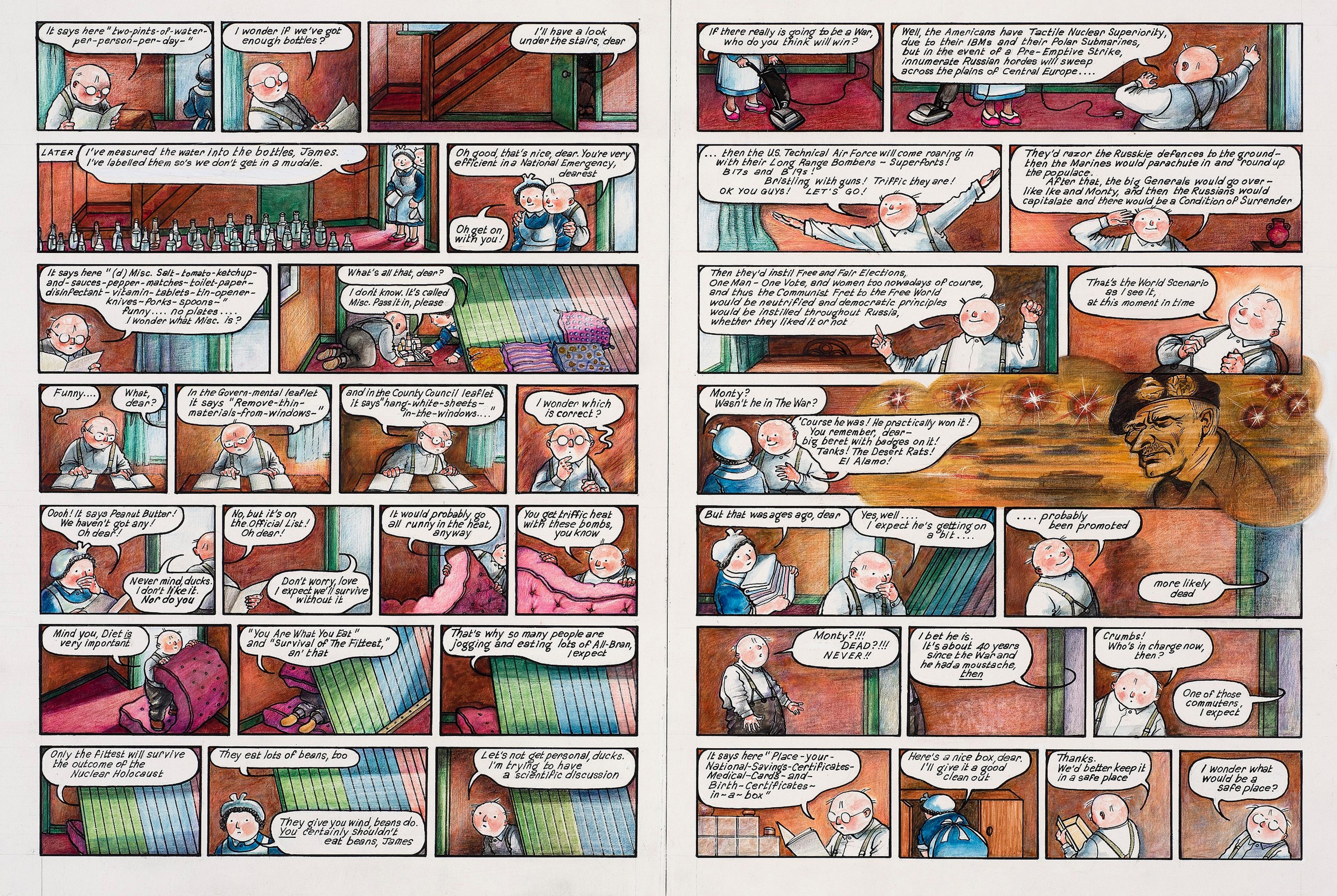

Some of Raymond’s books are about fighting power, or at least seeing power for what it is. Raymond didn’t think of himself as an activist, but many of his books from the 1980s critiqued people in power, including UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in The Tin-Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman. From the same time, his characters Jim and Hilda were based on his parents and featured in two books, Gentleman Jim and When the Wind Blows. In both, Jim and Hilda trust the police and the state, but are badly let down by wealth inequality and nuclear war.

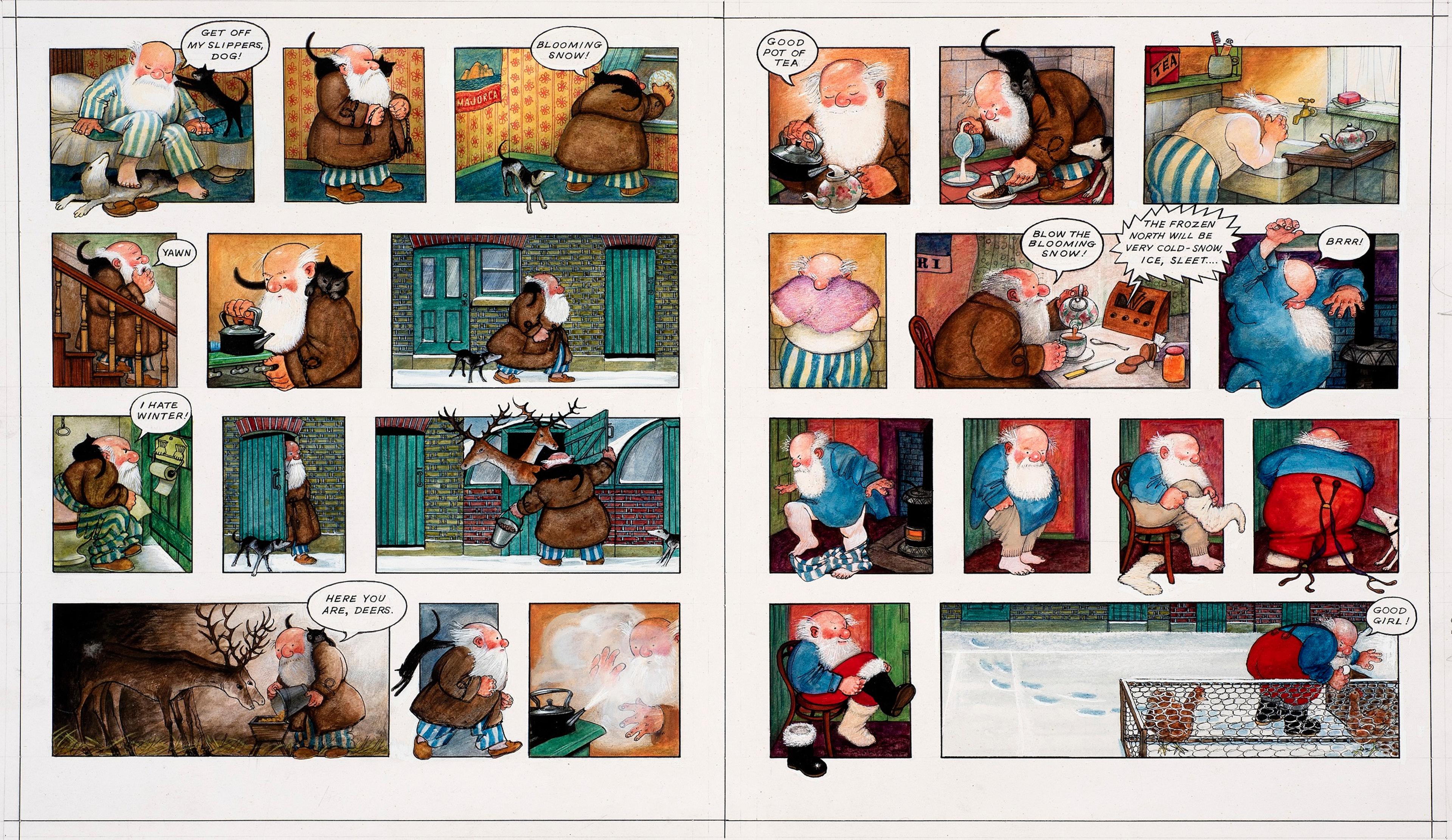

All of Raymond’s books were made completely by hand. He designed the layouts, made the illustrations and (usually) hand-lettered the typography. When I met Raymond as a (well over-keen) illustration student and talked to him about the way he sculpted his drawings with pencil and crayon, he said he did that not to create the soft and densely-coloured effect of his illustrations, but because he preferred dry materials that don’t involve washing up after.

I’m only concerned with getting the work done, getting it down on paper, getting it tidied up so you can get rid of it out of your head. What happens to it after that is another matter.

Although for Raymond, making artwork was the means to an end of finishing and printing a book, his original illustrations are just so beautiful: warm, precise and rich in detail. I was lucky to see it in 2018 when I visited his studio to gather artwork for a retrospective exhibition celebrating his work.

Raymond wasn’t sure about exhibiting illustration, saying it is “meant to be seen in the hand” and so “the whole operation [of an exhibition] is pointless”. But we are so pleased to be sharing his amazingly-crafted images with people across the UK. We hope that it will give inspiration to fans of Raymond, and introduce his work to new people too.