History of Press Graphics

by Olivia Ahmad, Quentin Blake Centre team

This month we’ve been reading Alexander Roob’s XXL title on 100 years of illustrated newspapers. Published by Taschen, it covers the explosion of illustrated journalism in Europe in the 19th century and its influence on modern art.

Content warning: this book includes classist, misogynist, racist and violent language and imagery reproduced from 19th and 20th century publications. These are not reproduced in this post.

Though we still use the term ‘newspaper’, most of us read the news online, and the editorial illustrators working with news media are making good on new digital possibilities. Last year, The Guardian seamlessly integrated animation, type and image transitions for its Cotton Capital series, while The New York Times used moving image for stories on subjects from ChatGPT to social media and faith.

History of Press Graphics is a super-sized account of what came before (at least in northern Europe and the US – the press graphics of other places are available). With hundreds of illustrations, it explores the rise of the illustrated press, from the anti-establishment pamphlets that were passed around England in the early 1800s to the newspapers and magazines that followed.

Author Alexander Roob begins in the 1500s with the broadsides (sheets of paper illustrated with woodcuts) that were sold by street hawkers. Over time, a small number of publishing houses sprang up across Europe selling prints on major events. Some illustrators used print libraries as reference to invent scenes from written reports while others, like Wenceslaus Hollar (who drew our site New River Head in 1665), visited executions and other events to create authentic eyewitness accounts.

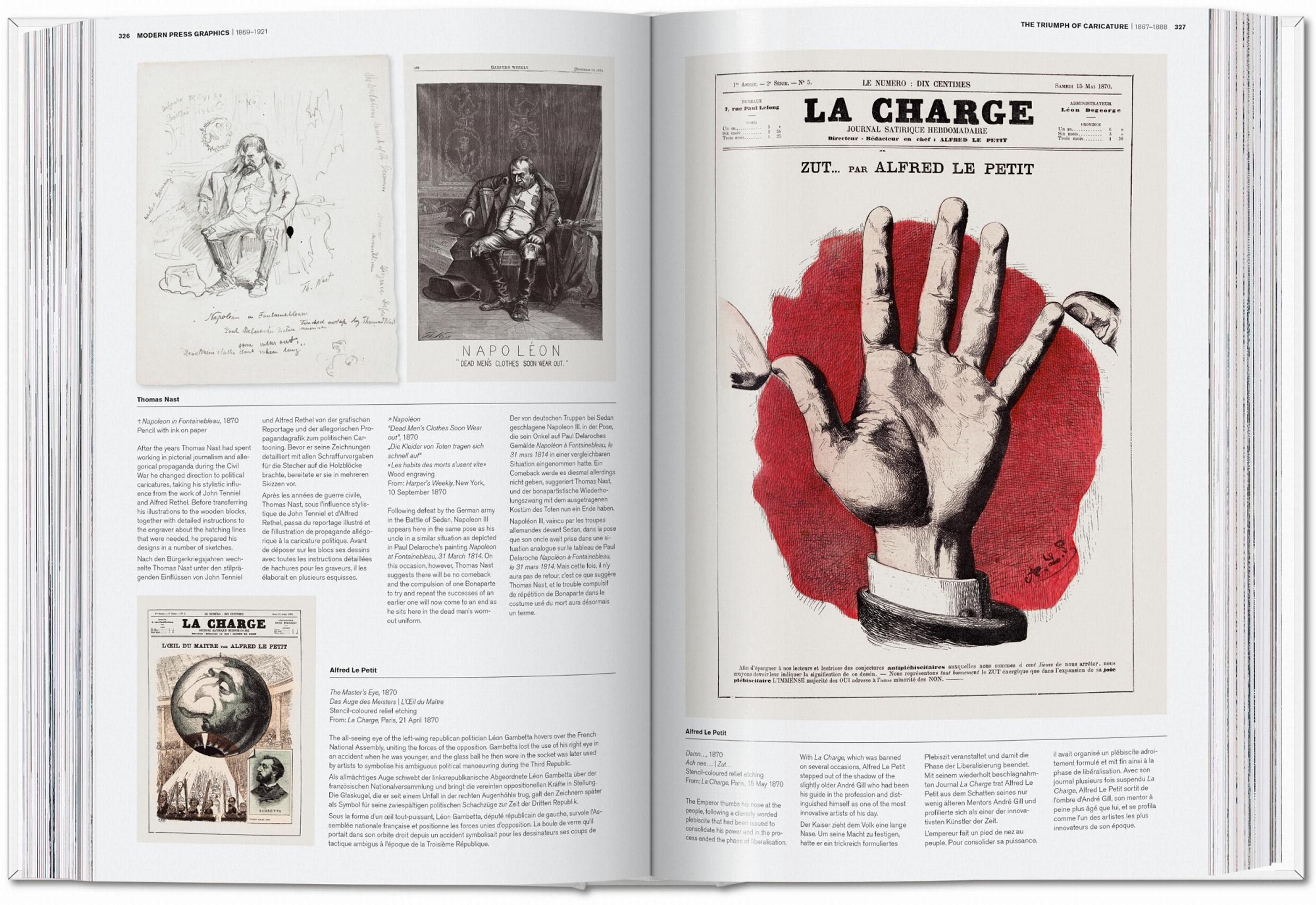

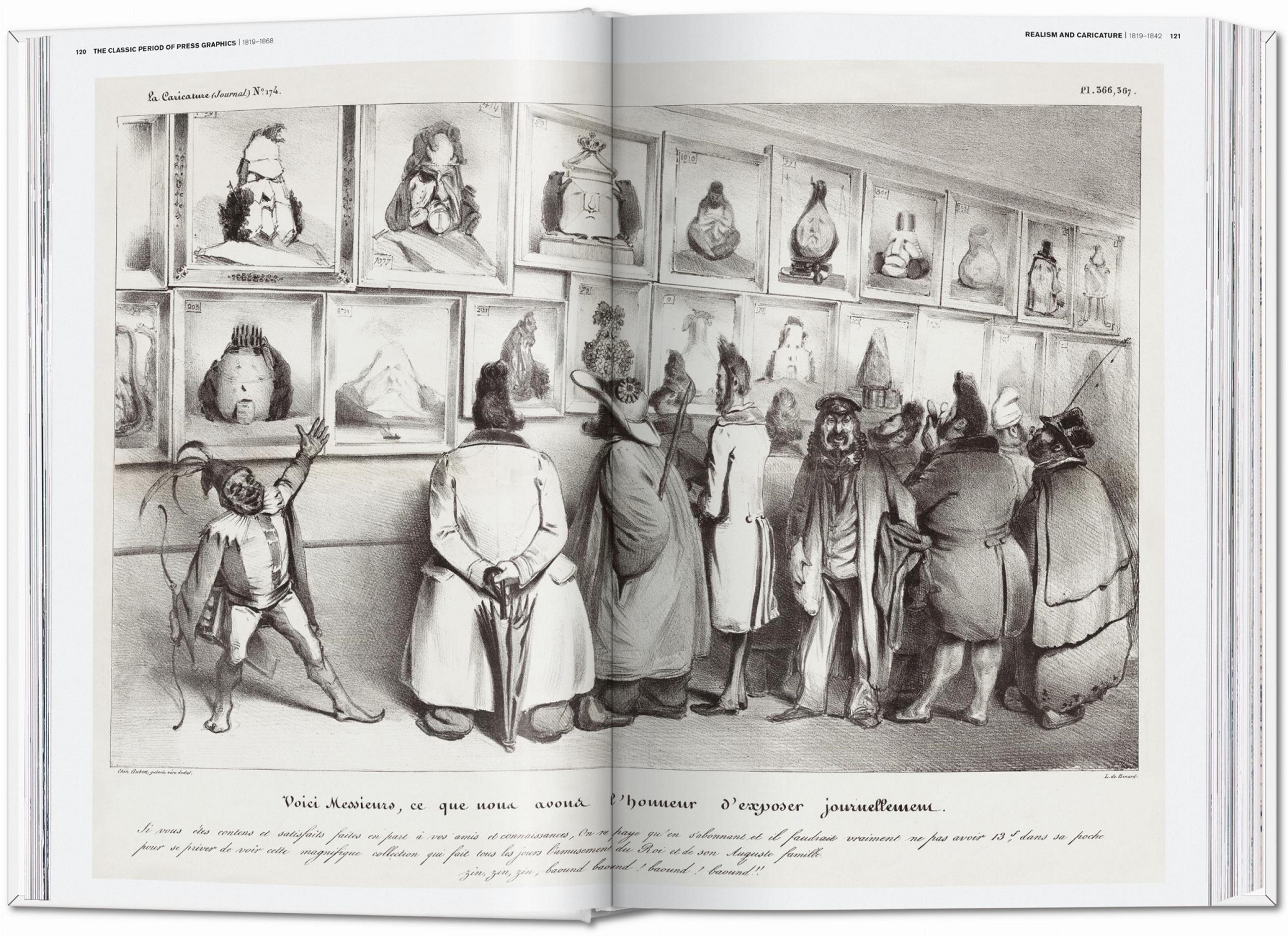

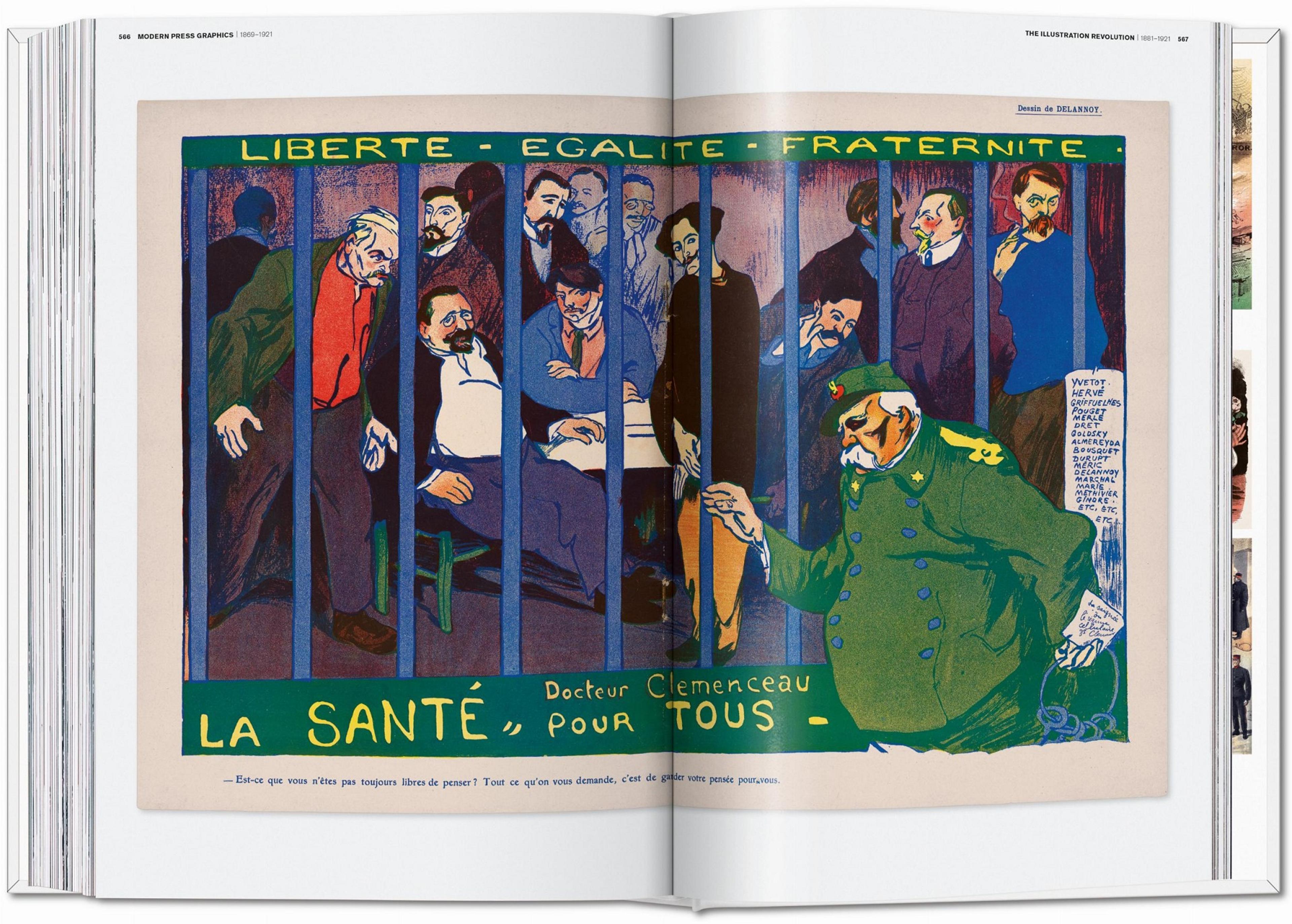

In the politically turbulent 18th and 19th centuries, caricatures (illustrations that exaggerated people’s features) were another way to report on current affairs. Royal and political personalities were ridiculed and criticised as a form of protest, with illustrators facing censorship and even imprisonment from a fragile establishment.

In France, Charles Philipon was taken to court for treason after publishing an image of King Louis Philippe as a rotting pear. The trial seriously backfired on the king when the jury agreed that the king’s head was pear-shaped. The pear became “a symbol of the stupidity and corruption of the political system as a whole, and spread like wildfire”, Alexander explains.

As well as targeting well-known establishment figures, caricatures reflected and reinforced racial and social stereotypes, coinciding with the adoption of the terms ‘stereotype’ and ‘cliché’ in the 1800s. “Many of the terms associated with the ideological implications of social and ethnic categorisation according to physical characteristics have been adopted from their use in illustrations for press” Alexander writes.

Illustration for the press evolved as new technologies developed and public appetite for news and debate grew. In 1814, The Times in London was using the first steam operated printing press. In 1842 the mass-circulation Illustrated London News was founded by a former newsagent who had noticed that newspapers sold better with illustrations. A report from 1879 explains how the paper’s in-house team divided the labour of image-making to meet demand:

For the production of a pictorial newspaper a large staff of draftsmen and engravers is required, who must be ready at a moment’s notice to take up any subject, and, if necessary, work day and night until it is done. The artist who supplies the sketch has acquired by long practice a rapid method of working, and can, by a few strokes of his pencil, indicate a passing scene by a kind of pictorial shorthand, which is afterwards translated and extended in the finished drawing. Sometimes more than one draughtsman is employed on a drawing where the subject consists of figures and landscape, or figures and architecture.

A drawing was made into a wooden printing block by a team of people. Blocks for large or complicated images might be cut into sections, with a different engraver working up each piece of the image. The finished blocks would be screwed back together then reviewed by a ‘superintending artist’ who tried to unify the image by blending the joins and bringing consistency to the image, often with only minutes to work before a deadline.

‘Special artists’ worked like reporters, making images on location and researching stories. “Some became celebrated in their own right” Alexander says, known for “travel books, autobiographies and public lectures.” Illustrator Melton Prior became one such personality, building his reputation on coverage of British colonial wars. His violent images were sometimes adopted by anti-colonial protestors as evidence of brutality.

Illustrator Thomas Nast took the role of both reporter and satirical illustrator in the USA, where the press developed a lively culture of debate after the American Civil War. Hugely influential on political discourse during his lifetime, Nast is best known for conceiving the donkey and elephant still used to represent the two major US political parties.

Nast’s contemporary Georgina Davis is the only woman press artist represented in the book. While it was undoubtedly a male dominated field, pioneering women made major moves as artists and engravers in the 18th and 19th centuries and should be included in any history of press imagery (we recommend Nicola Streeten and Cath Tate’s excellent book The Inking Woman for more).

The book ends by making connections between illustration and turn-of-the-century European art movements. Alexander describes how press graphics served as both popular news media and inspiration to avant-garde artists, with image-makers moving between the two fields. He explains that fine art later became segregated and elite, while press graphics were considered “ephemeral and unimportant”. History of Press Graphics makes a clear case for just how influential the illustrated press has been.

Get your copy here to support us and independent booksellers